With the recent observance of Remembrance Sunday, Armistice Day and Veterans Day, commemorating those fallen in the two world wars and all conflict thereafter, I was compelled to delve into the role of writing during wartime, specifically World War 1.

During the first World War, around 2,225 men and women from Britain and Ireland published poetry directly influenced by the war - some triumphant, most harrowing. At the time, it is reported that approximately 12 million letters were delivered to and from soldiers each week in a massive military operation involving a little known unit of the Royal Engineers - the postal section (REPS), The Army Postal Service (APS) and the General Post Office (GPO). The Boer war which had ended some 12 years earlier had set a precedent to servicemen that they would be able to remain in touch with families and loved ones at home.

Wilfred Owen poetry draft - image with thanks to the British Library

Wilfred Owen poetry draft - image with thanks to the British Library

Although the scale of World War 1 was unprecedented, the British Army recognised the importance of communication for the morale of the troops and letters to the Front were normally received within a matter of days from being posted - this fact astounds me. The Army considered the delivery of letters as of equal importance to the delivery of rations and ammunition for the overall war effort and as such, a global system was set up from the green pastures of Britain all the way to the mud and sludge of the front line. The story of how this incredible feat of humanity was achieved deserves its very own read, the BBC cover it beautifully when they asked; World War One: How did 12 million letters a week reach soldiers? To read more about the role of letters in the war effort, you may enjoy Martha Hanna’s, War Letters: Communication between Front and Home Front

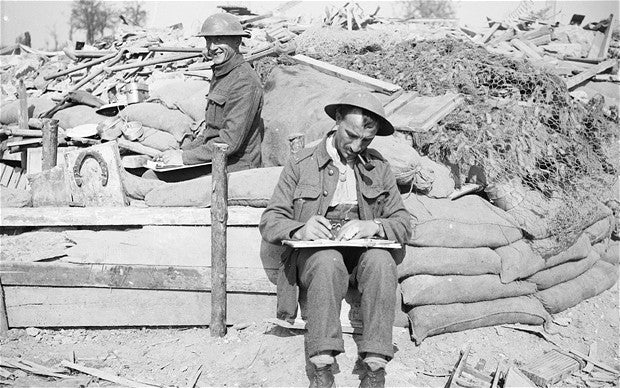

Mail being sorted at the front - The Postal Museum

Mail being sorted at the front - The Postal Museum

Publication from the Front line

For many, the process of writing at the front lines was a form of therapy and a way to process the experiences around them. Poetry from this period is possibly one of the most famous mediums of soldiers’ writing, with famous names such as Wilfred Owen, Lawrence Binyon, Sigfried Sassoon, Robert Grave dominating battlefield poetry with significant contributions from military medical staff such as Vera Brittain.

In fact, poetry from the front line was so much a prominent feature of WW1 that in March 1916, the editor of the respected trench newspaper the ‘Wipers Times’ printed his plea, that:

'an insidious disease is affecting the Division, and the result is a hurricane of poetry…. The Editor would be obliged if a few of the poets would break into prose as a paper cannot live by poems alone.'

Trench newspapers were widely circulated on both the Eastern and Western fronts, featuring writing from soldiers themselves and news from home, as well as satire, jokes and cartoons. Many regiments had their own versions of these publications and much joy was created within its pages - and publications featured excellent titles such as ‘spit and polish’ and ‘The Better Times’.

The first hand accounts from celebrated poets and authors, the verses and articles submitted to trench magazines and personal letters published in the years after the war by the everyday soldiers, nurses, and auxiliary/support forces are an incredible resource for historians and serves as a powerful reminder of the human condition and experience of conflict. One of the truly poignant aspects of much of the trench writing is the paradoxical mix of candidly ordinary words as well as the wrenching descriptions of the terrors faced by those whose hands steered the ink.

Perhaps the most famous poem from World War 1 is, ‘For the Fallen’ penned by Laurence Binyon which was first published in The Times in September 1914. Composed upon the outbreak of the war, this poem remains one of the best known elegies from the period as the fourth stanza is regularly recited at remembrance memorials.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Binyon wrote ‘For the Fallen’ on the cliffs of north Cornwall, however the impact of his words grew exponentially as the war continued and the stories of battles came back to Britain from the front line. The literature, poetry and art created in the theatre of war alongside letters from the trenches give the most detailed accounts of the events of World War 1 - from the horrors to the heroics, from the mundane to the extraordinary and most poignantly, the stories of love and compassion during a time where so many experienced the tragedy and terror of conflict.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton first introduced us to the adage ‘The pen is mightier than the sword’ spoken by the protagonist of his historical play,Cardinal Richelieu, in 1839. The oft forgotten suffix to the quote continues … ‘Take away the sword; States can be saved without it!'.

War time communication

During WW1 the importance of access to pen and paper really cannot be understated.

At the outbreak of WW1, electrical systems of communication had begun to be developed and war accelerated the advancement of technologies. That being said, non-electrical systems including carrier pigeons and dispatch riders were used alongside modern technologies such as telephone, wireless telegraphy and portable Morse code machines. But perhaps even more significantly, the role of writing and reading connected those at war with those left behind and became records for posterity for future generations, although the latter was not necessarily the intended purpose for many of those writing in the trenches or at forward operating bases across Europe.

Image credit: The National Archives

In the crucible of World War 1, the healing power of words was conceived through the concept of bibliotherapy which emerged in the US in 1914 and was impressively implemented by Helen Mary Gaskill who wrote this of her ‘war library’ in 1918:

'Surely many of us lay awake the night after the declaration of War, debating … how best we could help in the coming struggle … Into the mind of the writer came, like a flash, the necessity of providing literature for the sick and wounded.'

Gaskill and others like her provided books and literature to the injured and infirm in military hospitals and convalescence homes in Britain and further afield throughout the war. The value of reading and writing was very much a part of the healing process both physically and mentally during the war and in the years which followed. Which brings us full circle back to writing during World War 1.

Trench Tools: Lee-Enfields' and Eyedroppers

As you may expect there were significant challenges to writing in a war zone which extended beyond the obvious threat from the enemy. Although it is true that many adopted the trusty pencil as their tool of choice, the characteristics of pencil to be easily smudged and not as vivid on paper meant that fountain pens and trench pens were often a popular choice. It should be stated at this point that typewriters were available to clerical staff and higher ranking officers not on the front line, but most relied on a trusty fountain pen treated not just as a highly prized object, but for many as the apparatus which would - even if just for a moment - transform them home.

There is a significant amount of myth surrounding trench pens and inks, particularly regarding whether or not Parker held a large contract with the military to supply trench pens as part of ration packs (what a thought!) and whether bottled ink was forbidden or purely impractical.

Pen and Ink on the Western Front

When we think of fountain pens and World War 1 we think of the trench pens, these were specifically adapted designs suited to the conditions of warfare. However, the idea of a fountain pen which writes with ink formed from pellets/pills/tablets or ink powder predates WW1. Pens utilising dry ink forms were marketed not only to soldiers but also to travellers and the rural markets and schools specifically in locations where temperatures were particularly low such as in rural school buildings, farmsteads or anywhere in the mid to late 20th century which did not feature effective heating systems.

Ink experiencing very cold conditions would be prone to freezing which would cause the ink to spoil with a disturbance of pigment and settling of sediment making the ink unusable.These properties of ink remain perhaps little changed, but the world within which we place our bottles of ink has.

Reliance ink based in Manitoba Canada predominantly manufactured powdered and tablet form inks with direct advertising toward rural schools and small town communities in the decades before the war, and as such are used to evidence the apparent amnesia of such a product being in common use for certain communities prior to the growth in its sales during WW1. In fact, ink tablets and powdered inks were not entirely uncommon all the way through to the 1950’s and 1960's but by this point they had all but died out apart from among niche markets.

At the beginning of the war, the most common pen found among the allied forces was some form of the Safety pen, such as Waterman's ‘ideal’ safety pen, which was generally an eyedropper filled fountain pen. Having been released in the previous decade, Waterman's safety pens had already established themselves as quality writing instruments. To fill the safety pens, the writing point would be unscrewed and an eyedropper was used to fill the barrel with ink. This was not wholly practical as it required the user to carry additional equipment whether they were using bottled ink or dry forms. Powdered ink could actually be made with water or even beer, ale or wine as the sugar content of alcoholic beverages improved the saturation of the pigments. The regular unscrewing of the pen meant that threads could become compromised causing leaks and seizing which was problematic, especially as repair shops were hard to come by. Later iterations of the safety pen from companies such as Parker, Waterman's, and Mabie, Todd &Co would address this further with innovative design features.

The Waterman's ‘ideal’ safety pen’s nib retracted into the barrel with the aim to create a leak proof seal when capped or fully extended for writing purposes. In 1914, a Waterman or Parker would have cost the equivalent of approximately £45 for the former and £50 for the latter in today's money, this would have been quite out of reach for many of the lowest ranking soldiers of the war. That being said, those with the will or the means, would likely have preferred the safety pen over the more conventional eyedropper because it was considered more robust and was capable of holding more ink than the lever filler which was also reasonably popular at the time. Furthermore, those on the front line would not have prioritised the additional equipment required for an eyedropper pen or bottled ink for that matter. Onoto was another popular pen during this time and was reportedly the pen of choice for Winston Churchill who served as First Lord of the Admiralty during the early years of the war (involved in Dardanelles naval campaign and Gallipoli - leading to his demotion) later serving on the Western Front with the Army before finishing out the war as Minister of Munitions under David Lloyd George’s coalition government.

Parker’s Trench Pen 1916

Two years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Parker Pen Company developed the ‘Trench Pen’ marketed to the US infantry in a move of business acumen. There was certainly a market for an affordable and practical ink pen which would stand up to the challenges of near constant exposure, impractical storage conditions and frequent use. Although conventionally a Safety Pen at heart, the Trench Pen had a section in the barrel for storing ink pellets (also known as tablets or ink pills) - the user would simply pop an ink pellet in the barrel of the pen and add water.

Interestingly, the Parker Trench Pen, although widely marketed, never held any specific patent. English manufacturer Mabie, Todd & Co held trademark number 122,278 containing the term ‘trench’ from July 1918, similarly Edward K. Bixby in September 1918 held trademark 1,109,033 for a fountain pen with an ink tablet magazine under the barrel end blind cap bearing a very similar design and appearance to the Parker Trench Pen. Following the 1916 Parker Trench, many fountain pen companies released their own versions of trench pens though it should be noted that from 1688 in the UK, patents and designs for pens utilising dry ink and ink tablets where relatively common so although some may suggest that ink pellets were developed solely in response to the requirements of writing during the war, the reality is that they significantly predate 1914.

Parker sold ink tablets in either tubes or boxes costing 10 cents for 36 tablets (the equivalent of £1.89) and it took only 1 or 2 ink tablets to pill the barrel of any Parker pen. George Parker said of the time:

"Well, things continued about so-so until World War One came on. Then an idea came to me of supplying pens to the soldiers with the ink tablet furnished in the pens. In order to give the soldiers all the information as to where the ink tablets could be found, we put the tablets in a little blind cap at the end of the holder, and so that the boys would not overlook that this was a cap, we made it red, the rest of the pen being black. We sold vast quantities of these pens which were shopped through the War Department to the boys over in France, and it would not surprise me if there were many of the American Expeditionary Force who still have these fountain pens today."

There are discrepancies often cited regarding the Parker Trench pen, one being that blind caps would be red so as to be easily distinguished, however, of the remaining pens from the period almost all featured a black end cap. It would seem to me that this is but a minor detail but what is interesting is that there are relatively few surviving Parker Trench pens considering their mass production during their three year manufacturing run. It is plausible that this is mostly explained by the lack of distinguishing markings on these items meaning that there may be more original trench pens in circulation than have been identified or perhaps a more melancholic explanation may be that like many of the soldiers, these pens lay where they fell.

One such story emerged in 1996 in Loos-En-Gohelle, France, where a farmer unearthed the remains of a 29-year-old soldier who was later identified by his dog tags as Alexandre Villedieu who lost his life during the Battle of Artois in 1915. Among his belongings was a gold tipped fountain pen, still full of ink and engraved ‘Waterman’s Fountain Pen NY, USA. Aug. 4, 1908’. The Local historical Association cleaned it up and were able to write with the pen and its original ink remarking on the beautiful nature of the pen even after so many years in the ground.

Image with thanks to the Musée Alexandre Villedieu

Final Thoughts

As collectors and enthusiasts, the value of writing instruments is not something which is unfamiliar but the example of World War 1 is a moment in history where we really conceive of the power such a simple item can have for an individual. The years of the ‘great’ war were a time of astounding hardship and although the simple pleasure of receiving a letter from a loved one may not have changed the course of history, for many individuals it meant everything. Facilitated by the humble pen, we are able to appreciate the lives of those who came before us and sacrificed so greatly so that others may have a future. In this article, the pen is not the protagonist as it is in much of my ramblings, but rather is the trusty sidekick.

I leave you with the words of Binyon in full and some links to archives containing letters of the first world war.

For the Fallen

by Laurence Binyon

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children,

England mourns for her dead across the sea.

Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit,

Fallen in the cause of the free.

Solemn the drums thrill: Death august and royal

Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres.

There is music in the midst of desolation

And a glory that shines upon our tears.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again;

They sit no more at familiar tables at home;

They have no lot in our labour of the day-time;

They sleep beyond England's foam.

But where our desires are and our hopes profound,

Felt as a well-spring that is hidden from sight,

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known

As the stars are known to the Night;

As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust,

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain,

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.

Resources and additional reading:

George Kovalenko discusses his experience with Trench Pens sourced and repaired in recent years.

First World War Letters from the National Archives

The 'Letters to Loved ones' collection at the Imperial War Museum London

My Dearest - ‘My Dearest’ is an archive of over 400 personal WW1 letters between September 1915 and March 1919 plus photos and documents. These letters are easy to read, well written, informative and often humorous.

Wilfred Owen poetry draft - image with thanks to the

Wilfred Owen poetry draft - image with thanks to the  Mail being sorted at the front -

Mail being sorted at the front -